There is an element of suspense called the perception plot. It involves protagonists who witness something traumatic and then come to doubt what they have seen. This could be considered a subsidiary of the unreliable narrator plot with one key distinction: while the unreliable narrator intentionally deceives, the confused witness does it unknowingly.

A.J. Finn’s The Woman in the Window is one example of this. He creates a narrative in which the reader isn’t certain what the protagonist is really seeing. Anna is a heavy drinking agorophobic who stays up late in her Morningside Heights brownstone watching film noir. One night, in a scene ripped from Rear Window, she witnesses a woman murdered in the apartment across the street. Or does she?

Until the plagiarism scandal that roiled the author, I was an unabashed fan of this book. It was well-crafted, gripping suspense with a satisfactory ending. The author further messed with minds by giving a split ending, in which Anna had been right about some details but not others. That is a good way to both reward and tease readers.

In a similar vein is Penny Hancock’s A Trick of the Mind. Ellie is driving from London to the English coast for a New Year’s get together with friends. While on a dark country road, she thinks she has hit a dog and gets out to investigate. When she finds nothing, she continues on. Later that night, she is horrified to hear on the radio that a man was hit and hospitalized around that time and in that area. Could Ellie have blocked the trauma from her mind?

Until its over-the-top finale, this is a twisty, enjoyable plot that raises questions of whether we have moral obligations to those we’ve injured.

My most recent read in this area is Andrea Bartz’s The Lost Night. It combines a lot of appealing elements into a good read. Ten years ago, Lindsay was living with a group of friends in Bushwick (a section of Brooklyn) when Edie, the waifish center of the gang, shot herself. The trauma of this event caused Lindsay to lose touch with the remaining others. In the present, she decides to have dinner with one of them. During the catch-up, Sarah and Lindsay have noticably different memories of what happened in the hours before the suicide. This pushes Lindsay to investigate and come to terms with what happened to their friend.

Bartz smartly uses technology to fill in the gaps of Lindsay’s memory. With the help of a pregnant techie friend, Lindsay pulls up deleted emails and flip phone videos to recreate Edie’s final hours. In doing so, she discovers that she has in fact blocked out certain unpleasant truths.

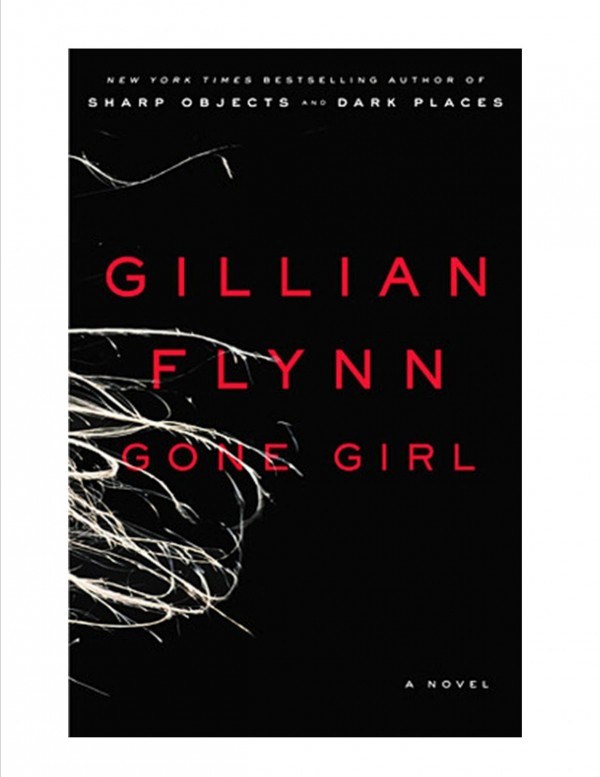

The Lost Night has an edgy, nihilistic tone that reminded me of Gillian Flynn’s darkest work. She has some insights into friendship and the kind of angst that accompanies the adulting years. If you don’t have time for it, I hear that Mila Kunis will be starring in the movie version.