My introduction to adultery was a very public affair. In the ’80s, rumors swirled that the fairy tale marriage of Prince Charles and Princess Diana was on the rocks. There were allegations, a separation, and finally an interview in 1995 watched by millions. “I don’t want a divorce,” Diana said. “(But) there are three of us in the marriage. It’s a bit crowded.”

A few years later, we were rocked by another scandal, this time on the other side of the pond. The reelected forty-second president stood in front of the cameras and addressed the nation. “Indeed I did have a relationship with Miss Lewinsky that was not appropriate. In fact, it was wrong.” Bill and Hillary Clinton were on the verge of divorce with the country watching.

There was a clear moral tenor to all of this: adultery was wrong, difficult to forgive, and hurtful to spouses and children. And, yet, curiously, the fiction produced during that time had a different set of values. Adultery was glamorized as a romantic ideal in two best-selling love stories.

In The Prince of Tides, Tom Wingo is a South Carolina teacher who travels to New York after his sister attempts suicide. There he begins a relationship with Susan Lowenstein, his sister’s psychiatrist. As they explore the siblings’ troubled childhood, Tom and Dr. Lowenstein fall in love.

In both the book and its Oscar-nominated adaptation, Dr. Lowenstein is the true hero of the story. She helps Tom unlock his emotional trauma and lovingly supports him. There is little attention paid to the professional lines she has crossed or to the harm being done to Tom’s three daughters. Compared to the excoriated Camilla Parker-Bowles, Susan emerges unscathed.

At around the time of Charles and Diana’s very public separation, a short novel was taking the publishing industry by storm. It was the story of a lonely Iowa housewife who encounters a man named Robert Kinkaid, who is in the area to photograph the famous covered bridges. While her family is away at the state fair, Francesca and Robert engage in a once-in-a-lifetime affair.

Like Dr. Lowenstein, Robert is a hero. He not only inflames Francesca’s passion but he gives her a way out of her unhappy life. The tragedy of the story is her inability to leave with him. When Kinkaid later dies, Francesca tells her children not to make the same mistake she did.

So why was adultery so romanticised in popular fiction, especially at a time when public examples told a different story? It’s possible that the authors, both men, were reflecting on the previous generation, when marriage was an obligation. Adultery was seen as a pleasant escape from commitment.

It was also an era when marriage was more commonplace. Francesca was a war bride who married a man she hardly knew. Tom Wingo was a repressed child rape victim. The suggestion here is that their marriages were artificial and their affairs were the real deal.

As we move into contemporary fiction, the perspective on adultery has changed. Cheating is no longer seen as part of the emotional catharsis of the protagonist. On the contrary, marriage is now viewed as fulfilling and adultery as immature and rightly doomed.

In Never Have I Ever, Amy reconnects with her high school crush Tig. Their brief romance was interrupted when they were in a car crash that killed a local woman. In the present, Amy is happily married with a baby. The temptation is there, though, and she flirts with the idea of crossing a line. Ultimately, though, Amy pulls back before anything gets out of hand.

In Happy and You Know It, Whitney is an influencer who falls for a friend’s husband. Their tryst is undeniably hot, but is ruined one day when Whitney’s babysitter cancels at the last minute. When Whitney shows up to a hotel room with her baby in a stroller, Christopher is over it. He has no desire to be a part of Whitney’s family.

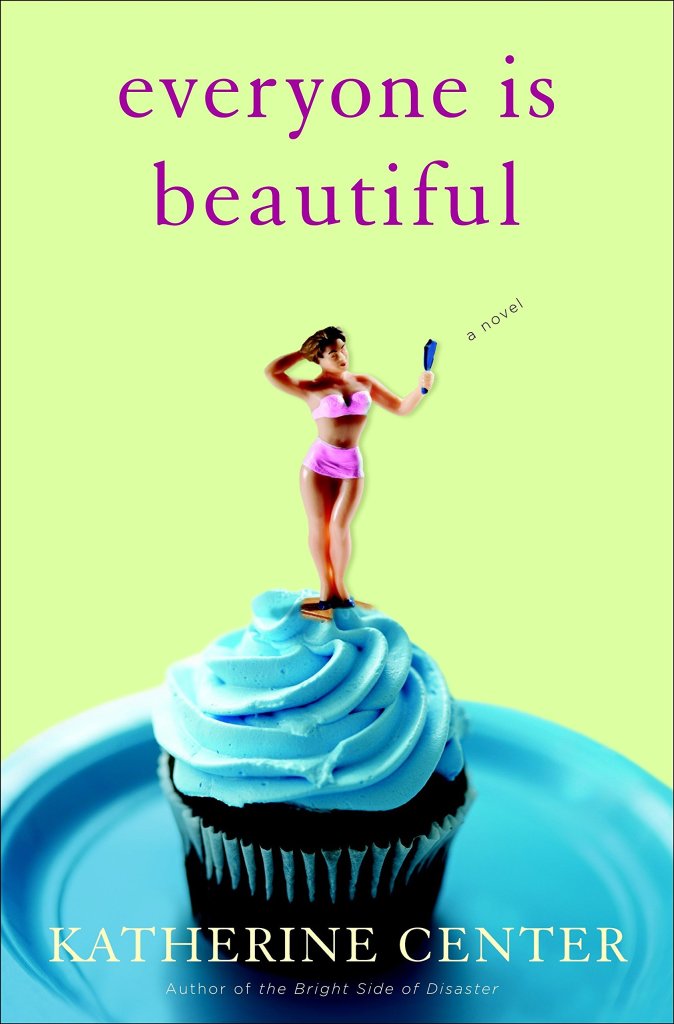

Everyone is Beautiful is another domestic novel that ultimately romanticises marriage over adultery. Lanie is the harried mother of three young boys. She and her husband relocate to Boston so he can pursue his music. While reconnecting with her photography, Lanie revels in being her teacher’s crush. She does not share Nelson’s feelings, but she enjoys the attention. When Nelson kisses her and declares his love, Lanie must grapple with her guilt. Curiously, though, she is never once tempted to take him up on it. Their brief encounter just reinforces how much more chemistry she has with her husband. Their intimacy and familiarity are the real turn on.

Clearly something has changed in fiction. Has marriage actually replaced the affair in terms of social desirability? The real achievement seems to be a marriage that is better than an affair. This could reflect a growing cultural maturity. With more people in therapy plumbing their issues, intimacy is getting better. Once an escape, affairs are becoming passe.

Or maybe this publishing trend reflects something more sinister. The need to keep up appearances – curating a fictitious domestic narrative – may have seeped into fiction. Everyone now wants to believe something about marriage which isn’t true.