A certain number of movies released each year start as books. There is a segment of readers who view movie adaptations with disdain, quick to point out how the nuanced, interior experiences of reading are lost when translated to cinema. There is a flip side, too, when movies require a certain tension and palpable transformation that books do not. A truly faithful adaptation of some narratives might result in a desultory and unsatisfactory viewing experience.

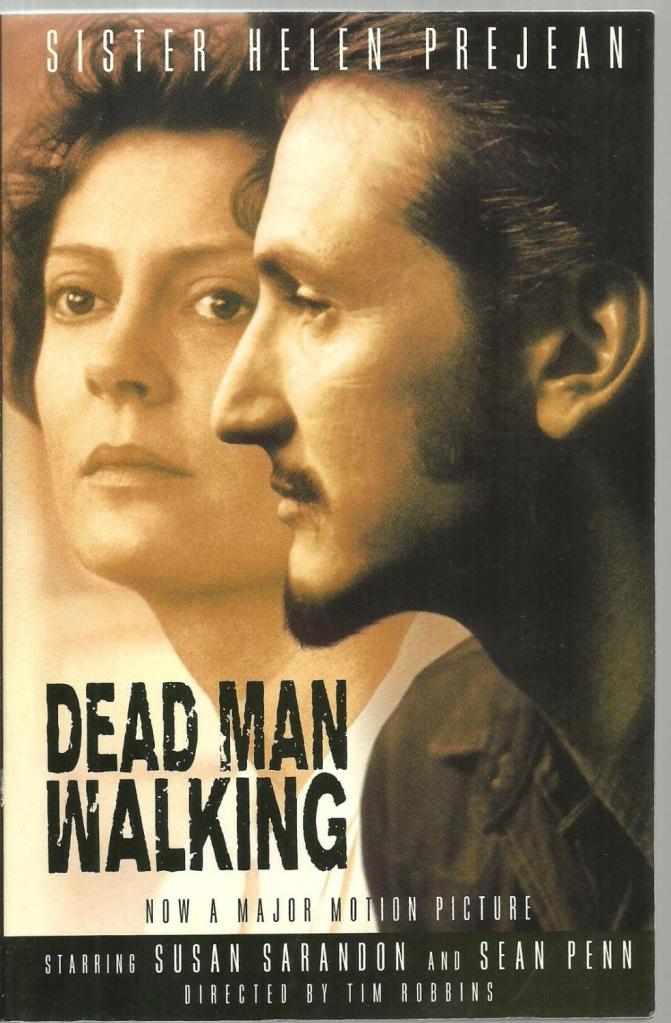

One interesting example of this is Sister Helen Prejean’s memoir Dead Man Walking, which was turned into an Oscar-winning movie. I was drawn to the book recently and enjoyed it. Then I rewatched the movie and things got really interesting.

In the early Eighties, Prejean had taken a vow to live and work among the poor in a neighborhood in New Orleans. I was immediately drawn into this story: the swamp heat of a Louisiana summer, the palpable danger of the area. What an inspiring sacrifice. Soon Prejean was exchanging letters with a death row inmate named Elmo Sonnier. She found herself drawn into Elmo’s story, eventually visiting him and acting as his spiritual advisor.

Elmo was convicted of participating in a double murder with his older brother Eddie. When his final appeal was denied, he was executed. His last words were an insistence that Eddie was the lone killer.

If you saw the movie, you are probably experiencing the opposite of deja vu right now. If this is not the movie you remember, no cause for concern.

A book like Dead Man Walking presents a challenge to adaptation. Elmo’s story, while intriguing, is not particularly cinematic. He doesn’t go through any kind of catharsis: there is no religious conversion, no last minute confession, no grieving family saying goodbye. In fact, he dies about a third of the way through the book. Later, Sister Helen encounters another death row inmate who went on an In Cold Blood type killing spree.

These two real life experiences are stitched together into one story with some crucial edits. In the movie, the killer and the victims’ families are composites of these two stories. They are given fictional names. Much of their dialogue is lifted directly from the book, but it’s as if two real life people become one character.

There also are some movie flourishes that aren’t present in the book. Early on in the movie, Matthew openly hits on Sister Helen. No surprise that this didn’t happen in real life.

There is also the matter of Matthew’s religious conversion. In the film, Matthew spends most of the time denying that he was more than an accomplice in the murders. Much of the tension comes from Sister Helen trying to get him to admit the larger role he played. They both have to reach a spiritual catharsis for the story to work: Matthew has to confess and repent, and Sister Helen has to get him there.

I suspect that this needed emotional arc may be why Matthew’s co-conspiritor in the film is largely absent. They do mention him, and he is seen in flashbacks of the crime. In real life, it was Elmo’s brother who masterminded the crime. Sister Helen visited with him, too. None of this happens in the movie.

The family connection complicates the story ethically and dilutes the intensity between the leads. Imagine the cover above with Sean Penn playing dual roles. It would be a different movie. By paring down a book to its best parts, Tim Robbins achieves a better story. It’s an inspiring example of editing.