“You were born where you were born and faced the future you faced because you were black and no other reason. I know your countrymen do not agree with me about this… they do not know Harlem, and I do. For these innocent people have no other hope. They are, in effect, still trapped in a history which they don’t understand; and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it. You know, and I know, that this country is celebrating one hundred years of freedom one hundred years too soon. We cannot be free until they are free.”

In 1965, when James Baldwin wrote those words to his nephew, he was a literary rock star of sorts. He had appeared on the cover of Time, he was a contributor to The New Yorker, and he and a group of other Black notables had met with Robert F. Kennedy to strategize how the Democratic party could better serve the Civil Rights cause. This is a level of celebrity rarely achieved by any writer. (I’m hard-pressed to recall any writer I have seen in the past twenty years on the cover of a news magazine.)There was a paradox to his success: at a time of deep racism, he achieved uncommon access.

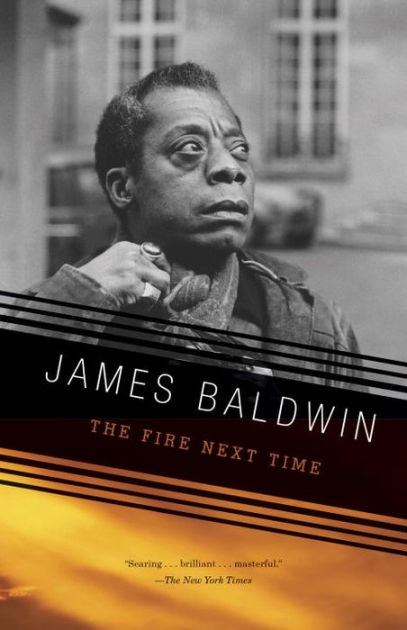

Reading his essay The Fire Next Time recently, I was struck by how little has changed since he wrote the words above. The “innocent people” he speaks of are White Americans who refuse to acknowledge the truth of his witness. We know more now about white fragility – the knee-jerk defensiveness that masks greater systemic issues – but it is still pervasive. Watch any conservative media and you will see a deliberate effort to minimize racism and mute testimonials like the one above. Corporate media (which is sometimes labelled liberal, although I think it’s more accurate to call it politically moderate) often tries to put a feel-good spin on even the most serious matters. It is in their interests to keep people shopping. There are many forces keeping people from honest reflection on these issues.

This is one reason why reading books is so important right now. To sit for an hour or two with a text like this is to hear a voice that is rarely considered in American media. Baldwin speaks in poetic language about the Harlem that he knows, about the casual racism he experiences when he travels below 125th Street, and about the competing temptations that the Church offers refuge from. There is a spare beauty in the language that puts you there.

You also read it now with the knowledge that Baldwin was a gay man in a world that didn’t accept him. It is impossible to read about his religious struggles without considering how his sexual identity intersected with ideas about salvation and punishment.

There is hope in reading this, too, with the awareness that his voice somehow rose above the conditions he so vividly depicts. Even in a time as obstusely racist as 1965, James Baldwin was a part of the literati, dining with artists and politicians. Someone was listening.