Have you ever read a novel written in diary form? By my estimate, there aren’t too many of them. It’s a peculiar choice for an author, an offshoot of the epistolary novel. Instead of writing to another, the protagonist is writing to himself. And how does it serve the story to frame the events this way? I will look at three reasons writers do this.

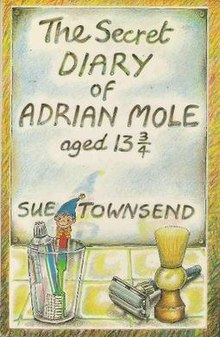

One of the best examples of this conceit is Sue Townsend’s The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole. It’s a book series which begins when the protagonist is nearly fourteen, finding his way in class-conscious Thatcherite England. I first discovered these books when I was a bit older than Adrian, studying for a semester in Germany when I was seventeen. I could relate to Adrian’s earnest optimism and painfully awkward yearnings. The reader slowly figures out what Adrian does not, which is that it will be nearly impossible for him to achieve his romantic and social goals. He has been born into a rigid caste system from which a love of books and learning is his only escape.

This series wouldn’t work nearly as well if it were written in the third person. A key part of its charm is Adrian’s lack of self-awareness and the reader being in on that. He has a naive faith in equity that will be dashed again and again. The reader can see what he can’t. It’s heartbreaking.

So shading a character is one reason to write in diary format. Another reason to do it is to dupe the reader. I have written before about Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl. In the first section of the novel, the narrative shifts back and forth from Nick’s first-person to diary excerpts from his missing wife. This is an effective choice for two reasons. First, the reader gets to know Amy’s backstory, which makes her more than just an absent crime victim. Second, it’s a creative way to show flashbacks of Nick and Amy’s courtship and early marriage. And then, because Gillian Flynn is a first-rate writer, she uses the diary format to upend the narrative. Turns out Amy wrote the semi-fictional entries to frame Nick. Gotcha!

In a similar vein, Alice Feeney’s Sometimes I Lie uses a diary to trick the reader. Amber is thirty-five, married to Paul, and in a coma. While she is unconscious, we get a narrative from her about the events leading up to the car accident which put her there. Included in it are journals from when she was a teenager. In another brilliant twist, the reader learns that the police have made a mistake. The journal they uncovered does not belong to Amber but to another character close to her. The use of a nickname in the entries has thrown everyone off.

While not a common conceit, journal entries in fiction can strengthen both characterization and plot. In the three examples I offer, the narrative wouldn’t work as well if written in a more standard format.